I don’t recall what sparked the idea, but at some point in early August, I decided to hike the La Cloche Silhouette Trail in Killarney Provincial Park. The Silhouette Trail is notorious for being difficult, both in terms of the hike itself and also in making reservations. Most campsites are snatched up as they become available.

Soon after, I managed to snag a workable 4‑night clockwise progression of campsites for mid-October:

October 11: H16 — Three Narrows Lake

October 12: H23 — Moose Pass

October 13: H37 — Silver Lake

October 14: H47 — Heaven Lake

After booking the campsites, I actively ignored the trek to concentrate my attention on our other trips that summer. We returned from our B.C. road trip in late September and I became preoccupied by La Cloche Silhouette. Lily, Porthos, and I had done several “hard” day hikes on the trip (Sea to Summit Trail near Squamish, Frosty Mountain Trail in E.C. Manning Park, and Towab/Agawa Falls Trail at Lake Superior Provincial Park). Our successful completion of these supposedly hard trails inflated my confidence and ego.

As October 11th approached, I read about the trail, scrutinized the elevation gains, participated in online discussions, and bought new gear (satellite communicator, trekking poles). But it was advice from my neighbours from across the street, who had tried and abandoned the trail years ago, that I ignored at my peril: every ounce of gear matters. Instead of listening, I expressed that my biggest worry was finishing each day quickly and getting bored alone at camp, you know, because I’m so fit and invulnerable.

–

As is traditional in this household, no matter how big the adventure, we always pack our things the night before a departure. As I slowly assembled my pack, Lily suggested that bringing Porthos could make the trip less lonely. Dogs are permitted, but most sources recommend against taking them due to some technical scrambles. Porthos is almost 11 years old, but he’s a very fit senior pooch, and he managed all those difficult trails in September without a problem. I agreed to bring him, adding his sleeping bag and pad, because the nights would be cold and he doesn’t have a particularly thick coat.

My pack weighed about 38 lbs with all my essentials, a full 2 L water reservoir, and the dog’s accoutrements. Not bad. Porthos would carry his own food, bowls, and brush. And then, against Lily’s advice (and my neighbours’) I made a crucial error—I added a further 12 lbs of camera equipment. She tried to convince me that this is a personal trip and that my phone should suffice for pictures, but I couldn’t be swayed. And that’s why my pack totalled 50 lbs.

For context, I’m 175 cm (5’9”) tall, about 65 kg (143 lbs), and 41 years old. So my total hiking mass would be 193 lbs.

October 11 — Day 1 — George Lake Campground to H16

I woke up at 05:50 after going to sleep at 01:45. Porthos and I managed to leave the house at about 07:15. The drive to Killarney from Toronto is a good 4‑plus hours without stopping, but I needed a washroom break and a fuel stop, so we arrived at the park office shortly after 11:40. By the time I parked the car and got ready, it was past noon. I took the following photo at 12:24 at the trailhead.

We encountered five day hikers between the trailhead and the ridge that overlooks a small stream between Lumsden Lake and a shallow marsh. It became exceedingly quiet beyond that point.

Two bridges span that stream; the first was collapsed, but the second was standing. After crossing it, we climbed up to a flat quartzite ridge whose distinguishing features were sharp striations and thick patches of moss and other short plants. That’s when I lost our path for the first of many times to come. I spent several minutes wandering around the rocky dome and referring to my digital copy of Jeff’s Map of Killarney before finding where the trail resumes.

About 7 kilometres into the hike, while I was slowing down to adjust my heavy pack due to discomfort, Porthos alerted me about something behind us. A man emerged from a bend we had just passed and quickly caught up. He had an apple in one hand, and chewing through a bite, asked which campsite I was headed to.

“H16,” I responded.

“I’m heading to H17. Good luck!” And then he was off, passing me effortlessly and continuing along the uneven, slippery rocks like nobody’s business.

Porthos was hungry and tried to catch up with the man because he associates apples with treats. I became envious of his quick pace and made a fruitless attempt to match it before realizing it was too fast and risky. You don’t have to hike far from the trailhead to see how hazardous the La Cloche Silhouette can be. Rain earlier that morning left the very rocky ground slick, with countless hidden hazards beneath the autumn leaf litter.

About two-thirds of the way to our campsite, we reached the base of the monstrosity known as The Pig—an 18-degree ascent stretching roughly 500 metres up a gulley of rocks ranging in size from softballs to beach balls. Any part of me not already drenched in sweat at the bottom was soaked by the top. Porthos, meanwhile, bounded ahead easily, stopping every so often to watch me struggle behind him. Like the eye of a hurricane, the short level section at the top offers only a brief reprieve because it’s followed by an equally long and difficult descent. Too focused on my footing, I missed the marker where the trail splits from The Pig, and ended up stumbling onto several parked boats and the rusting remains of an old truck by the shore of Three Narrows Lake. I knew about the truck from Jeff’s Map, but hadn’t planned on seeing it. After a few photos, Porthos and I climbed back up a quarter of the way to rejoin the proper trail.

Shortly after The Pig, we reached a dam separating Three Narrows Lake from Kirk Creek. Signs warned against crossing, but the shortcut was too tempting. Killarney Outfitters’ trail guide cautions, “Once Kirk Creek is reached, it may be tempting to cross here to avoid taking the trail all the way around. This course is inadvisable as the trail is difficult to rejoin upon reaching the other side!” Wrong—it was simple to rejoin: head up, up again, and left.

The 2.5 kilometres from the dam to campsite H16 were thankfully flat, though riddled with muddy, overgrown marshes. By then I’d stopped caring about getting dirty; pain had taken priority. The 50-pound pack was wearing me down. My shoulders felt tenderized by the straps, sending sharp spasms through my middle traps and into my neck. My hip flexors cramped from an overtightened belt. A pressure blister had begun forming over a bony prominence between my SI joints. Even the soles of my feet ached. Porthos, meanwhile, was doing well—just hungry.

By the time I saw the H16 markers and followed the path into my reserved campsite, my body was finished. I was looking forward to relief and quiet, but instead, saw a pitched tent. Two guys emerged from the left. I don’t recall our exact exchange, but I was tired, sore, and in no mood for surprises, so my greeting wasn’t exactly warm. They’d started at H6 that morning, aiming for H19, but one of them had developed severe knee pain somewhere along the way. They decided to abandon their plans, turned back, and chose H16 as a stop for the night.

H16 is an odd site. There’s excellent water access, but the best tent pad sits deep in the woods, far from the fire pit, which, for some reason, has a clear view of the thunderbox.

I told the guys I’d set up near the water and fire pit. My tent was small enough to tuck into a flat space between trees. They’d already gathered deadfall and started a fire, though it was mostly smoke. I had no time or interest in a fire, so I suggested they move their wood elsewhere.

Camp chores are tedious and time-consuming. I had to pitch the tent, set up my sleep system, filter water, feed Porthos, assemble the stove and pot, and change into clean clothes—all before dark. The sky had cleared, but the sun was sinking fast and the air had cooled. While the stove warmed water for my freeze-dried meal, I took a skinny dip in the lake to rinse off. I lasted about thirty seconds, just long enough to wash the sweat off.

The cold water and rough rocks made my feet ache even more. After drying and dressing, I rinsed my dirty clothes, wrung them out, and hung them to dry. The pot had boiled by then, so I rehydrated a meal and made tea. I ate it with whole wheat pita and shared some with Porthos.

We crawled into the tent around 21:00, long after dark. I’m generally uneasy at night in the wilderness, but the faint chatter from my neighbours was oddly comforting. That night, I dreamed that a large animal was sniffing around my tent, poking its nose into the fabric, and punching it in the face.

October 12 — Day 2 — H16 to H23

I woke about an hour before sunrise. The air was chilly—enough to keep me in the tent another thirty minutes before committing to the day. A thin fog drifted over the lake, and the clothes on the line were still damp.

I lowered the bear hang, boiled water, and made oatmeal and coffee for breakfast. Porthos got a generous serving of kibble followed by spoonfuls of oatmeal. He loves People Food™.

Once the sun cleared the trees, I realized the clothesline was still in shade and moved it into sunlight to help things dry faster. Even so, I had a slow start, leaving camp at 10:30—about an hour after the two guys had set off.

Finding the correct route out of camp proved annoyingly difficult. I went down the wrong path several times, adding a few hundred metres of back-and-forth before locating the actual trail. Strangely, it passes within about twenty metres of the thunderbox, which is in direct view.

The trail started off flat and easy, following the same pattern as the landscape north of the Kirk Creek dam. Despite the mild terrain, the weight of my pack turned uncomfortable, then painful, within the first two kilometres. I had to stop often—leaning the pack against a tree or rock, or bending forward at ninety degrees with my arms braced on the trekking poles—anything to relieve the pressure and restore circulation to my shoulders and waist.

I met two pairs of hikers walking counterclockwise. The first, two women between H18 and H19, greeted Porthos and exchanged some pleasantries. Later in the afternoon, near the quartzite ridge between H21 and the waterfall ascent, I met another pair—also two women—on the second of their three-day circuit. An impressive pace. Their first day had taken them from George Lake to H37, where I was scheduled to arrive the following night. This encounter was the inception of a thought: could Porthos and I make it back to the car from H37 in a single day instead of two? I wondered…

There wasn’t much time to dwell on it. Minutes after parting ways, we hit our first real obstacle. The quartzite pass ended abruptly, and the trail dropped steeply into a stream valley. The descent isn’t long—barely a blip on the elevation profile—but the initial rocky funnel was technical and awkward with a heavy pack, and completely impossible for Porthos without help. This is where a dog harness with a sturdy handle is non-negotiable. Lifting him down short ledges is easy enough, but here the rock shelves were chest-high, slippy, and uneven. On its own, the scramble down was manageable. What made it arduous was Porthos panicking. First, he refused to approach me, and then retreated back up the rocks, either afraid I’d make him follow or hoping to find his own route. He usually can, but this time there was no alternative path. It was either down or hike back to the car.

It’s hard to get Porthos to obey gentle commands when he’s afraid. That isn’t to say I didn’t try, but after several minutes of baby-talking from a narrow ledge of broken boulders, my patience faltered. I snapped and yelled. It wasn’t my proudest moment, but it worked. As the echoes faded, his head appeared from behind a rock a few metres above. Hesitant, he climbed down toward me. When he came within reach, I grabbed the handle of his backpack and held tight. With my free hand I found a secure hold against a rocky edge, shifted my footing, and lowered him to the ledge below. There was nowhere to escape from there, so he waited while I climbed down again, found my balance, and hoisted him further down. Bit by bit, rock by rock, we scrambled down past the rockfall to the forest floor.

At the bottom, the trail followed a narrow valley beside a stream leading to the next obstacle, the waterfall ascent. Jeff’s Map describes it as “Medium Cascade,” AllTrails says you must “Scale Waterfall,” and Oleksandra Budna describes it as “hiking down through a waterfall (I’d like to emphasize the word through)…”

I’d been dreading this climb all trip. Then we got there, and it was pathetic. There was water, and it was technically falling, but calling it a “cascade” felt generous. The only workable route ran to the right of the trickle, over large rocks and tree roots. Only once did Porthos hesitate at a ledge, but a firm, “get your brown ass over here!” did the job. I suspect the earlier rockfall taught him to trust the logic of being lifted by that backpack handle.

The stretch between the waterfall and campsite H22 was steady and uneventful. For roughly half the distance, lakes sat to our left and ponds to our right. Campsite H22 was empty. It’s perched on the southern shore of a nameless lake with steep water access. Not long after passing it, Porthos and I began the long descent toward H23, our home for the night.

H23 was one of the worst campsites I’ve ever stayed at. It sits deep in a deciduous valley between two steep hills. By our arrival on October 12, many of the trees were bare, and the ground was carpeted in damp leaves. I wouldn’t see sunlight again until climbing out the next morning.

But wait—it gets worse! A meagre creek trickled along the bottom of the valley. To reach it, I had to clamber 5–8 metres down over slick rocks and roots covered by leaves, then squat over wet rocks while collecting water from a stream barely deeper than my filter’s intake throat. It took patience, but I eventually filled my four-litre capacity.

Then came the matter of bathing. I was soaked in sweat and the air temperature was dropping, but I needed to wash before changing into warm clothes. For a moment, squatting naked over the creek and splashing myself seemed workable—until I pictured Gollum hunched in his cave. Instead, I returned to camp, stood naked and barefoot on my small foam sitting pad, and washed with cold filtered water, one handful at a time. I had an audience of one: Porthos watched the entire ordeal. It wasn’t pleasant or thorough, but it worked. At half a litre down, it was the most efficient shower I’ve ever taken.

The valley darkened quickly, and camp chores remained. I found two trees for a clothesline and hung up my damp gear. Porthos ate his dinner and a little extra. I ate my freeze-dried pasta with black beans. The bear hang took nearly twenty minutes because none of the nearby trees had adequately strong horizontal branches. I recommend using a bear can instead of relying on hangs.

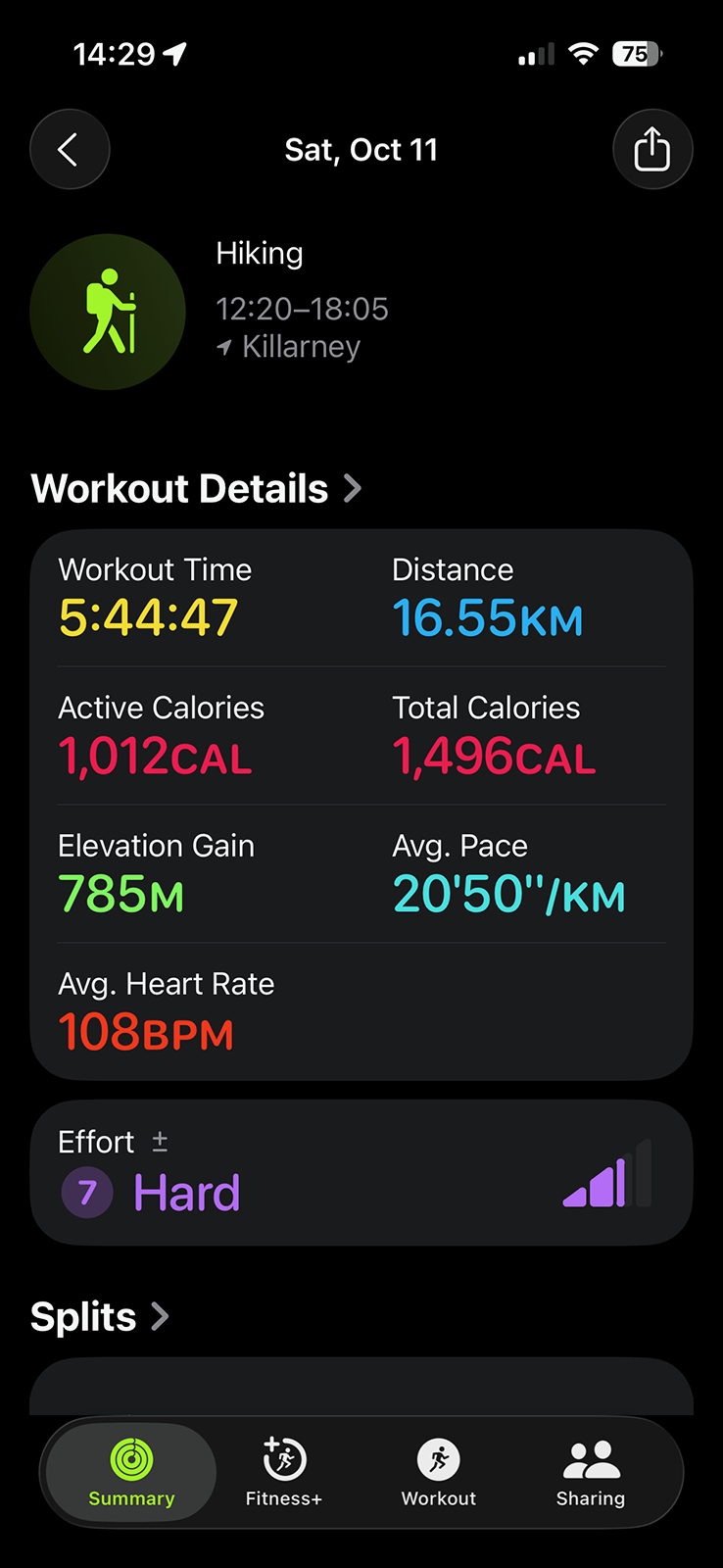

I was tired but not sleepy, so I lay in my sleeping bag with Porthos snoring beside me and checked the Apple Fitness summary. The numbers didn’t add up. The expected distance between H16 and H23—listed as 16 kilometres in both Killarney Outfitters’ chart and the digital version of Jeff’s Map—showed as 19 kilometres on my Apple Watch. I started to suspect drift in the numbers around H20, but it became obvious when the watch chimed 16 kilometres just before the waterfalls. Poor signage might have added some extra distance, but not three full kilometres.

Around 02:00, the waning gibbous Moon rose over the valley walls, throwing moving patches of light across the tent.

October 13 — Day 3 — H23 to H37

I woke around 07:00. It was still twilight, but bright enough to manage without lights. Unfortunately, the damp valley had soaked my tent—inside from condensation, outside from dew—and every piece of clothing I’d hung to dry was now wetter than the night before. Fantastic.

I recorded a short vlog over breakfast, mostly complaints about the campsite and my pack weight. The location was so miserable I didn’t bother taking pictures; the image below is a frame from the vlog.

Packing up felt like playing The Floor is Lava. I tried to keep everything off the wet leaves, hoping to avoid adding more water weight to the pack.

We left camp shortly after 09:00. Within minutes of crossing last night’s miserable creek, the trail launched straight into one of our biggest climbs—about 130 metres of elevation over 800 metres of distance. It was too early for this shit. To make matters worse, I’d forgotten to apply deodorant. Halfway up, during a rest stop, I removed my pack and shirt and sprayed a generous amount. I already felt gross, but I didn’t need to stink, too.

At the top, we were rewarded with the best view so far. The forest stretched below in copper and crimson patches of autumn colour. Porthos rolled in the tall grass like a lunatic while I stood catching my breath. That’s when I noticed something odd. Someone had abandoned a heavy-duty tripod and a Manfrotto fluid head on the rocks. I’d long since accepted the burden of my own ‘lightweight’ tripod, but this thing was enormous. I guessed it weighed 15–20 pounds. Whoever carried it up here must have decided a few thousand dollars in gear was worth less than the energy to haul it out.

After a short break, we descended into the forest, moving across alternating ridges and lowlands. That’s when my frustration with the trail markers hit its peak. Every new bald peak of quartzite meant slowing down to hunt for cairns. Some were huge, others barely knee-high; but all too often you couldn’t see the next one from the last.

We were deep in the most remote part of the loop, equally far from both the trail’s start and finish. Getting lost here would be a problem. Even down in the open forest parts of the trail, the ground was carpeted in leaves that erased evidence of the path. I relied on secondary clues: footprints in the mud or subtle compression in the foliage confirmed I was on track. Other times, those traces vanished and the faint trail forked with no marker to guide me. My patience wore thin. I cursed Ontario Parks’ aloud! The standard should be simple: if the path isn’t obvious year-round, the next marker should always be visible from the last. Anything less is negligent. And cairns should be distinct—spray paint them blue or something!

About five kilometres in, we entered a short but brutal section of wet forest that felt like walking through a 200-metre carwash. Wet leaves soaked me with every step, the trail turned to mud, and visibility dropped to a few metres. It would’ve been a terrible place to surprise a bear.

We soon emerged into an open deciduous valley where the trees had shed half their leaves. There we passed the only backpacker we’d see all day. I say “passed,” because the man gave a quick hello and kept walking without reducing his pace. Not everyone’s a talker.

Around the ten-kilometre mark, we came to a shallow stream. Porthos wasn’t interested in drinking directly from the source, so I took off my pack and filtered fresh water for both of us.

Just before stepping off the last rocky ridge northeast of Boundary Lake, I took my first fall. After a brief rest and snack, I had set off too fast and stepped from soft moss onto a leaf-covered slab. The leaves concealed wet rock beneath; my foot slipped, and I went straight onto my back and slid several metres before stopping where the rock met the dirt. Porthos slid down after me, seemingly amused. I lay still for a moment, waiting for pain that never came. The pack had cushioned the fall.

The trail then descended through forest toward a small stream feeding Boundary Lake, crossing a shallow rock channel. Another kilometre brought us to a fork in the trail that lead up to Silver Peak. In the distance, a group of day hikers was descending. It was late afternoon, and my watch claimed we’d already exceeded the 18 kilometres between H23 and H37. The map showed we were close, but the lack of precision was irritating.

The next 1.6 kilometres were pure bliss: wide, well-travelled, two-lane trail that’s nearly flat and with perfect footing. We made excellent time until the next fork—where a sign announced H37 was 1.1 kilometres away. That final stretch was a steep, rocky slog.

The 100-metre side path to H37 featured a steep descent with a taunting view of the campsite below and no easy way down. But the struggle was rewarded. The site was exceptional: three tent spots, excellent water access at two sides, and a fire pit that was nestled between rock slabs which were perfect for sitting. The only flaw was the placement of the thunderbox, which was positioned too prominently.

We arrived just as the sun was setting, which forced me to rush through camp chores. In hindsight, I regret not photographing the cliffs across the lake awash in golden sunlight.

The north side of camp offered an easy descent to the water. Several boulders disappeared into the cold water, with a flat one just under a metre below the surface. It was a perfect platform for a quick rinse.

While refilling water on the south side, I realized we had neighbours at H38, just seventy metres away. They called out a greeting, but Porthos started barking at them before I could respond. From my vantage point, their site looked treacherous: sheer rocks and poor water access.

That night, I reflected on the past three days. The pace was taking a toll, and my watch’s inflated distance readings were hampering my morale. My clothes were perpetually damp; I was down to one clean shirt and pair of underwear. So I kept thinking back to the two women doing a three-day circuit. Surely Porthos and I could skip overnighting at H47 and just finish the trail tomorrow. It was tempting, but I was uncertain about the true distances.

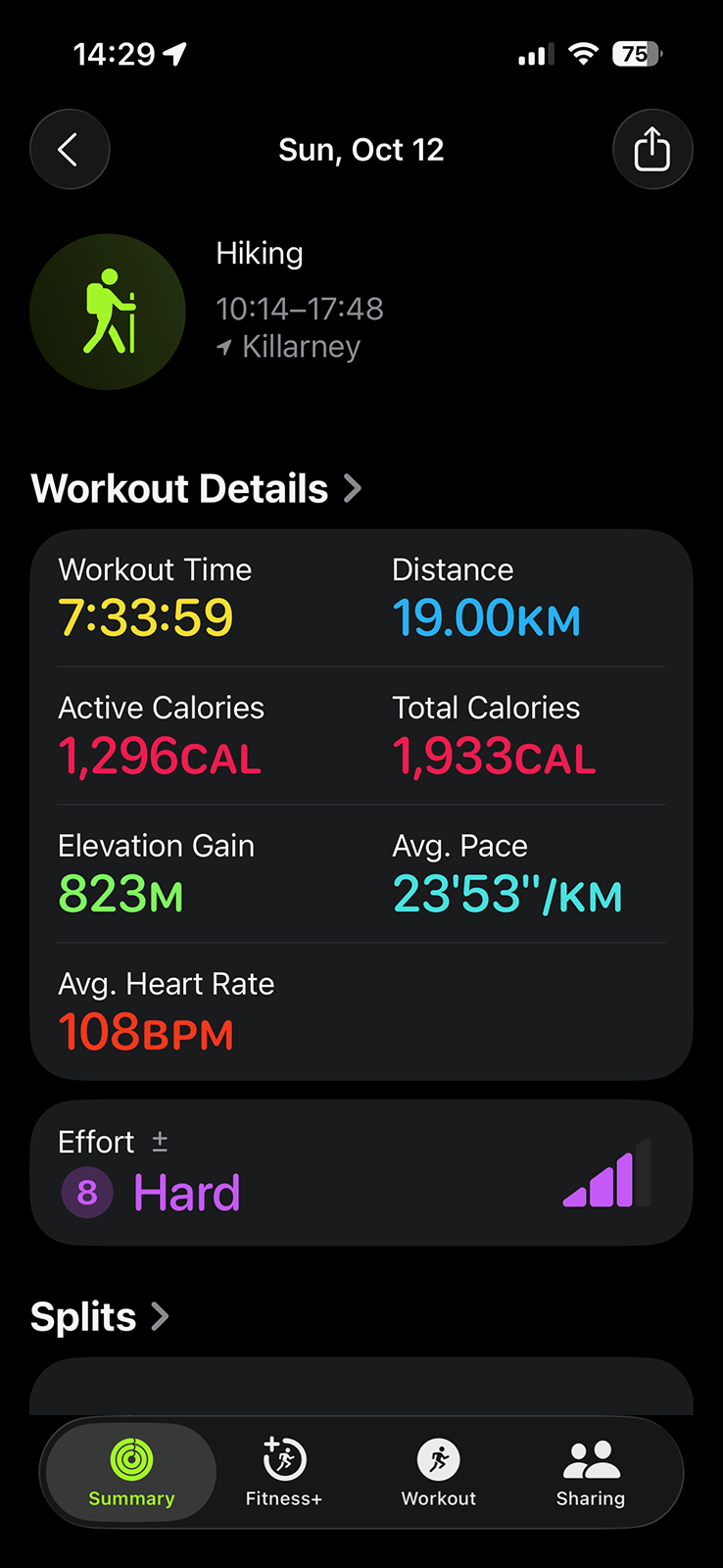

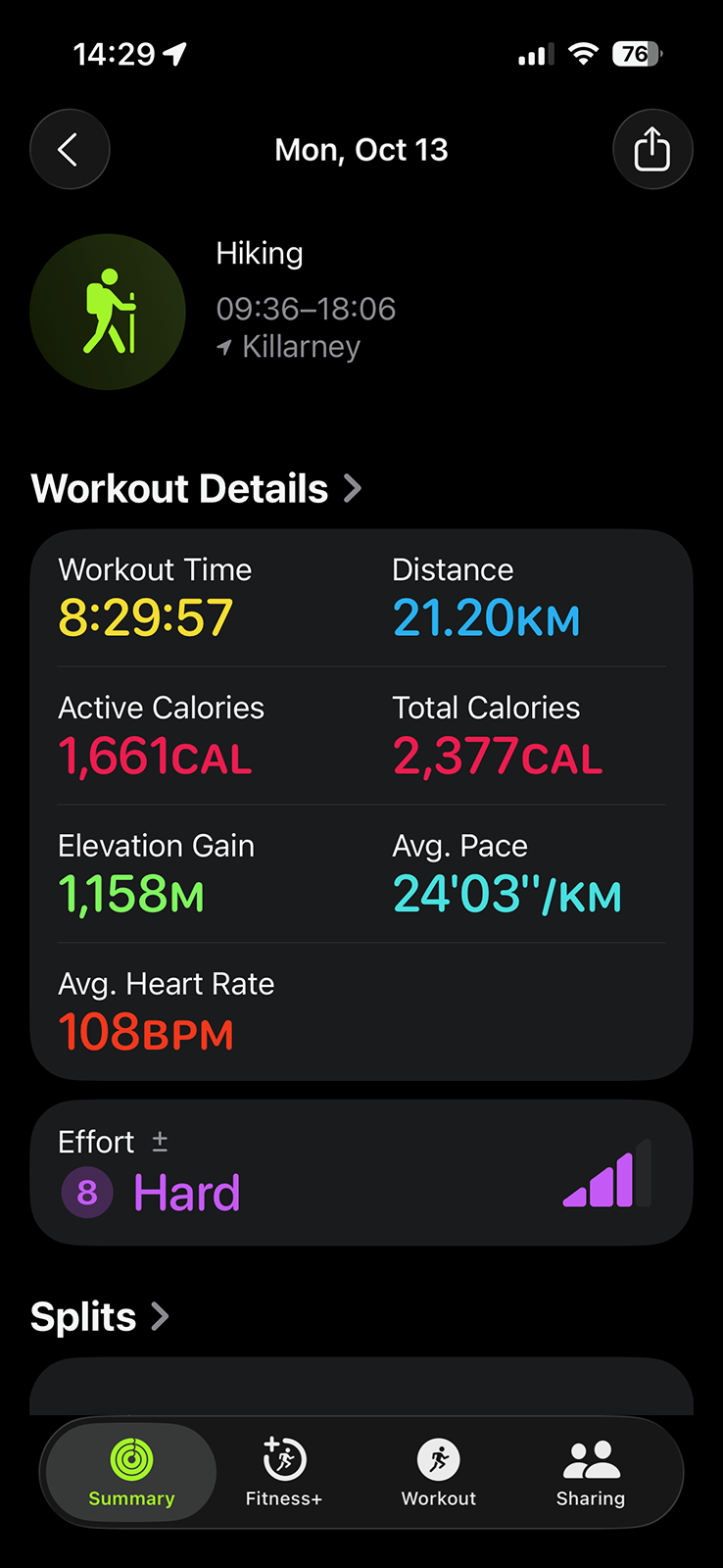

I texted the idea to Lily via my satellite communicator. Between her replies, I double-checked the map and meticulously measured the distances myself. Every source agreed on the numbers. And yet, my watch showed three extra kilometres on today’s hike—21.2 instead of 18.2 between H23 and H37.

By my measurements, the distance from H37 to the exit should be 22.5 kilometres. Lily’s research suggested closer to 26 or 27. That meant potentially 15–20 percent more walking. I was willing to push myself, but I had to consider Porthos’ endurance. I resolved to stop thinking about it and sleep. We had to get an early start the following morning, regardless of whether it’s our last.

October 14 — Day 4 — H37 to ???

I woke just before 06:00, beating the alarm by a few minutes. Dawn was still an hour away. I lay there planning the day: leave as early as possible and aim for H47. If we reached it before 12:00, we’d rest briefly and push for the finish. But if Porthos showed fatigue—or if we arrived later than 12:00—we’d stick to the plan and spend the night. Hiking unknown distances in the dark wasn’t worth the risk.

Rising early meant navigating the campsite by headlamp. Between breakfast and packing, I set up my tripod to capture a time-lapse of the sunrise over Silver Lake. Predictably, I was a slowpoke at packing up. We left camp just before 09:00—my earliest start yet, but still later than I had hoped—and had three hours to reach H47.

Leaving H37 was as difficult as entering it, just in reverse. We climbed over bald rock and through several ascents before rounding the southern shore of Silver Lake where I stumbled upon an excellent unofficial campsite (with fire pit!) just steps north of the trail. It had a great view of both H37 and H38 across the water.

The first two kilometres were pleasant and the path was easy and shaded. Then came the day’s pattern: climb, cross, descend, repeat. A gentle forest walk would end in a steep 45-degree ascent. We’d pull ourselves over roots and rocks onto pale pink slabs of quartzite, navigate our way across sparse markings, descend again through root tangles and stone, and start over. Over. And. Over.

Somewhere north of Bunnyrabbit Lake, Porthos and I met a friendly pair of backpackers, a father and his son. When I mentioned my watch was recording longer distances, the younger man said his Garmin was doing the same. This non-scientific sampling gave me some reassurance that my Apple Watch wasn’t the problem.

We arrived at H47 on Heaven Lake at 11:58. In fact, we almost walked past it. Heaven Lake is a depression within a large dome of quartzite (Check for yourself on a map). The pass leading to it from the east was poorly marked. Cairns help, but they show where the trail is, not where it’s going. When you can’t see the next one, you rely on secondary clues—like flattened grass and footprints—but these can vanish easily with a shift in light or angle.

That’s how we almost walked past H47. Fortunately, the lake to my right looked suspiciously scenic, so I checked the map and found that we were nearly on top of the campsite. We stopped to rest at the water’s edge. Porthos ate his second full meal; I chewed a crunchy bar and finished my trail mix.

Heaven Lake is small but beautiful; it’s about a third the size of Silver Lake. Its elevation gives a clear view south toward Georgian Bay but makes it breezy. This gave me a chill after a few minutes of rest, so we didn’t linger. Surprisingly, I had cell reception (Telus/Koodo), so I called Lily and told her to expect us that night.

About half an hour later, along a wide forest path, we met two more backpackers—men in their early thirties and experienced. The chattier one sized me up and, after glancing at the camera gear, admitted he was surprised I’d made it this far with so much weight on my back. He showed me his official (and waterproof) map of Killarney Park, featuring the distances and elevation profiles between every campsite. According to him, we still had six to eight hours of hiking ahead. Not great. Not terrible.

For the next fifteen minutes the trail descended steadily over even ground. Until it didn’t. The path tilted upward into a steep climb tangled with roots and boulders. Two markers mocked me on the way up: “If hiking were easy…” read the first. “They’d call it canoeing :)” followed the next. In my mind, I fantasized being Homer Simpson and strangling the writer just like Bart. I hated them.

By now, I resented both the quartzite and forest sections equally. The forest teased me with restfulness only to force me into another climb. Porthos held up remarkably well—leaping up ascents when he could make the jump—but his fatigue was visible. Each time I paused to readjust my pack, he’d sit or lie down instead of sniffing around. The longer our breaks, the slower his restarts.

The trail markers on the final approach to The Crack were maddening. We needed to cross a small rift and climb out, but only two markers were visible—one on each side—with no hint of where to actually cross the gulf. I eventually found it, but lost time in the search. (It’s to the left and down; not straight or right.) Then we climbed to the quartzite outcrop leading to The Crack, and it was brutal: big steps and steep ledges, slippy surfaces, and constant glare from the low Sun to increase the difficulty of scanning for cairns. I heard the voices of day hikers ahead before I saw them. We reached the main lookout just before 16:00. Ten or so people were scattered around, surprised to see Porthos appear from the wilderness. I gave myself ten minutes for a snack, to enjoy the view, and to take a tripod photo of the two of us.

I lost my path entirely when leaving the lookout point and asked a couple for directions.

“Where’d you come from?” they asked.

“From about seventy kilometres the opposite way.”

They pointed: north first, then bend south. Soon we entered the narrow corridor flanked by sheer cliffs—a feature familiar to me from pictures. The descent in and out was simple enough.

Then came the obstacle that stopped me cold: a massive heap of fallen boulders with deep dark gaps between them. I stood there, my brain crashing from incomprehension. Surely this wasn’t the way down. The same couple appeared beside us.

“You’re looking at it,” they said—and started descending carefully.

Fuck me.

Photos don’t capture the scale of this rockfall. The rocks range in size from beach balls to compact cars, and the spaces between them could swallow a person whole. I was more worried for Porthos because one wrong step could be catastrophic. For a moment, I considered climbing down first, leaving my pack at the base, and coming back for him, but that would consume precious minutes and leave him panicking alone. Instead, in a first on this trail, I leashed him and we inched our way down. At each ledge I’d descend first, put down my poles, anchor myself, grab the handle of his backpack, and lower him carefully. Then we’d repeat. Again and again.

It took us ten hair-raising minutes to descend the rockfall. There were two hours of daylight and an unknown distance remaining.

The next section opened onto the longest quartzite dome of the day. Fortunately, it was easy to follow thanks to cairns having bright blue posts, some even fitted with directional blazes. What luxury! If only the rest of the trail were this considerate.

Soon we entered sparse forest where the path was wide and obvious. It curved around Kakakise Lake and crossed a crescent bridge with an awkward slant. A few minutes later, a fork announced the split between The Crack Trail and the Silhouette Trail, complete with a bright blue sign: 6.2 kilometres to go. Right about then, my satellite communicator chimed with a message from Lily confirming the remainder was mostly forest. A welcome relief.

No dillydallying. We pushed west at our fastest safe pace. The sun had maybe an hour left, though it would disappear behind the hills much sooner. I snapped my final photo about thirty minutes past the sign, a last glimpse of sunlight. Several boggy stretches followed, their unsteady footbridges more hindrance than help, but nothing compared to what had come before.

By early twilight we reached the beaver dam crossing at Wagon Road Lake. The campsites on both sides, H51 and H52, were empty. We finished our last snack bars in silence. Porthos rested in the grass while I geared up for nightfall with two headlamps. The weaker Petzl around my neck to light the ground immediately ahead of my feet, and the stronger Fenix on my head for range and spotting markers.

Darkness fell quickly after the dam. Porthos stayed close behind instead of leading. The first couple of kilometres were mercifully easy—flat, smooth, and mindless. I was in glee when a sign announced 600 metres to the trailhead. But that excitement was premature. I know what 600 metres feels like. This wasn’t it. It was the longest 600 metres of my life.

Halfway through, the trail threw one last curve ball at us. There were a handful of steep ascents and descents, and short rocky traverses. I kept having to remind myself this wasn’t some celestial punishment for my initial arrogance, just mindless geology.

From the final ridge, I smelled woodsmoke and saw campfire flickers below. This last descent was harrowing: darkness, fatigue, and high ledges that required lower Porthos with my tired arm. I lost balance once and landed hard on a sharp rock, my left glute taking the full impact. It hurt deep but wasn’t serious. Had I fallen a few inches further left, I would’ve landed squarely on my tailbone. The potential of that injury made me clench.

And then, suddenly, we were on a road. We’d reached the George Lake Campground. It’s funny how I didn’t remember it being so sprawling. Every trail guide recommends parking your car at the exit so you can finish and drive off immediately. Our late start on day one had ruined that plan. Now, exhausted, we trudged another 1.4 kilometres through the campground. Porthos lagged heavily; he’d had enough, and so did I.

My feet were blistered, toenails bruised, and the skin was raw where the backpack straps rubbed against my clavicles and pelvis.

The car was a comforting sight. I dropped the pack in the hatch, changed shoes, and fed and watered Porthos before settling him into his nest in the back seat. I called Lily and told her we survived.

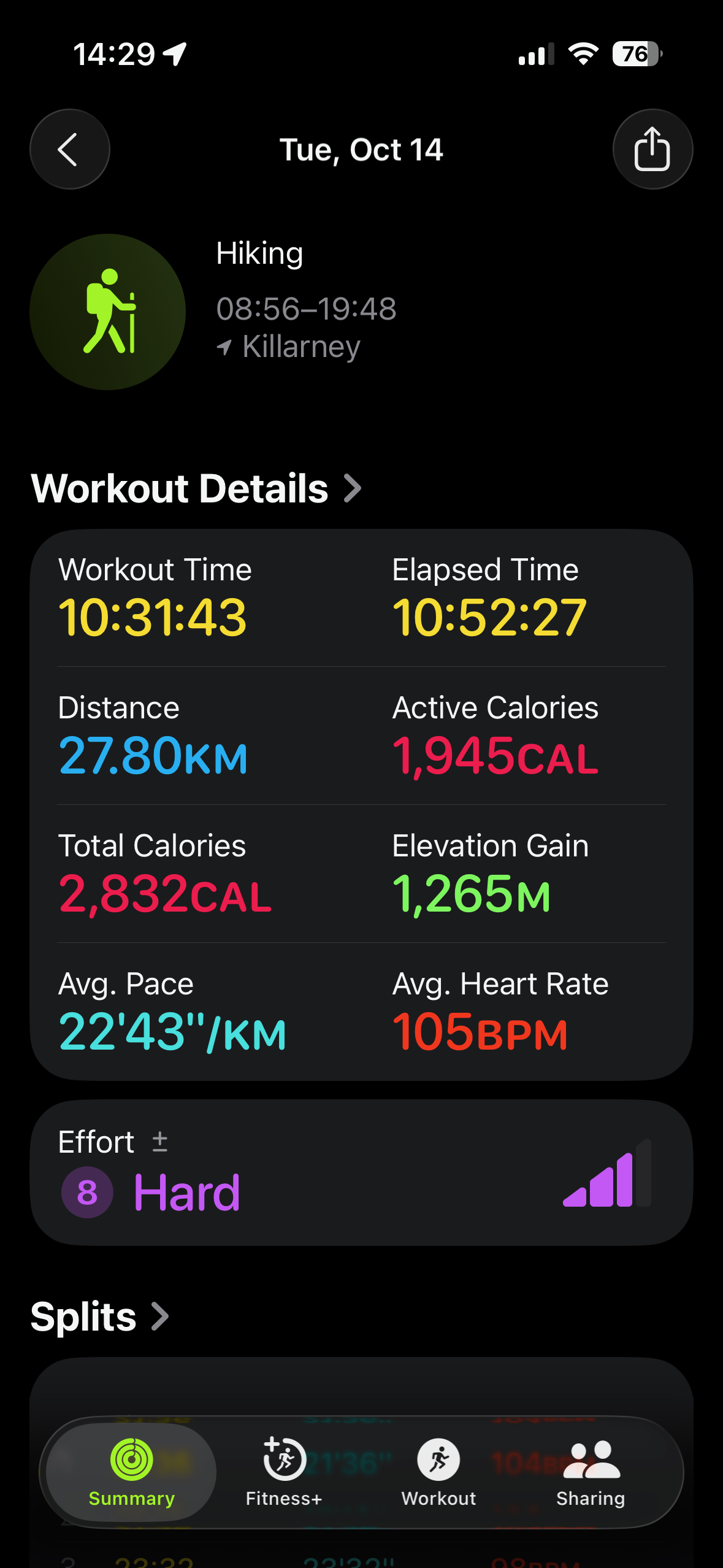

According to my watch, Porthos and I covered 27.8 kilometres from H37 to the car at the western trailhead. Subtracting our walk of shame through the campground makes the distance between H37 and the clockwise exit 26.5 kilometres. Lily’s research was correct.

Curiously, though I’d cursed the trail from day one, the moment I reached the car, I started thinking about everything I’d change for next time.

The drive home was uneventful. I developed a dull ache around my kneecap while driving along the two-lane road from Killarney to Highway 400. Later, I stopped to refuel at an Indigenous gas station where I limped into the store for an energy drink. Quite aware of my smell, I made it quick. The knee pain subsided before Parry Sound, where I treated myself with a Harvey’s veggie burger with not one, but two (!) patties and large fries. Caloric.

I pulled into the driveway behind our house just after midnight. Porthos and I both limped out of the car.

When Lily saw me shirtless later that night, she said I looked like I’d been beaten up.

She was correct. The La Cloche Silhouette Trail licked me good.